Fatima Bhutto praises pro-Palestine student protesters

14 May 2024

In this eloquent essay reprinted from Zeteo, Fatima Bhutto, the Pakistani novelist and public intellectual who was an undergraduate at Barnard College in New York at the time of the second Intifada, places the courageous stand of college protesters today in historical perspective.

In Defense of America’s Student Intifada

Students protesting Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza have ignited in me an electrical feeling I had almost forgotten: hope.

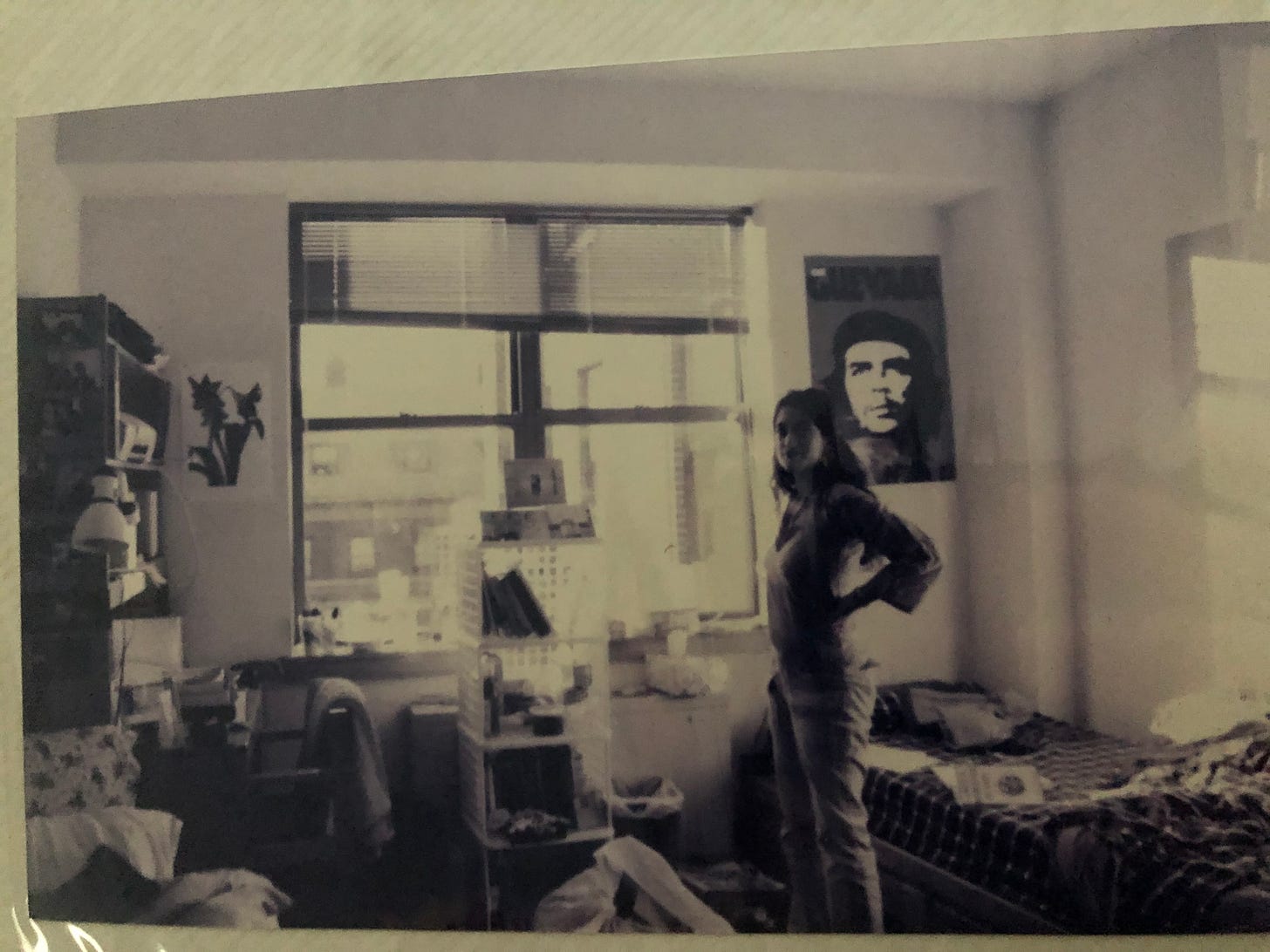

When I was a freshman at Barnard College, two months into college life and terribly homesick, the second intifada erupted. Sitting in my dorm, I watched the footage of Israeli soldiers killing 12-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah as he crouched behind his father in Gaza. The young boy’s body was contorted in fear as his father tried to shelter him from Israeli bullets. Even in the grainy footage, you could see Muhammad crying out, helpless and afraid. I have never forgotten his face. It has been seared in my memory ever since.

That horrific killing and the tumultuous events in America and worldwide would become the backdrop of my college life – Israel’s brutality in trying to quash the second Intifada, 9/11, the neoconservative U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, George W. Bush’s first term, the abuses at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. Students across campus felt the same horror and fury that I did, and we gathered in defiance of the violence of the ruling classes – to protest it, to speak for a better world, and to learn from each other. Watching the students leading today’s protests sweeping college campuses, including at Barnard, I see that what we had then was just a spark. Today, it is a conflagration.

Growing up in Syria and coming from a family that was resolutely pro-Palestinian (my father wore a keffiyeh on his wedding day), I had been raised in the shadow of Israel’s violent occupation and apartheid. But it was not until college that I had ever attended a protest in solidarity with dispossessed Palestinians. During the second intifada and throughout my time at Barnard, an affiliate of and located across from Columbia University, I wore a keffiyeh in the winter to protect against the cold and went to all the protests, sit-ins, class strikes, and die-ins. It was in New York, on the same campus police swarmed this year, that I joined hundreds of other students to call for divestment from Israel even then, though at the time, it seemed a faraway dream. The gatherings were what we could muster against a cruel and indifferent world, and those of us who attended came with but slivers of hope in our hearts that one day, someday, that world would tremble with solidarity for Palestine. I truly never thought I would live to see the day. But as Malcolm X said to a woman despairing that there were too few like-minded people to make a difference, “Never let your enemy tell you how many of you there are.”

Even though I was a college student at the paranoid time of the Patriot Act and pervasive anti-Muslim surveillance and policing, I never felt unsafe at any of the protests. I felt reasonably assured that my university wouldn’t hand me over to the state for reading Franz Fanon or the Oxford University short history on terrorism. The president of Columbia at the time never called the NYPD to put down any of the student protests. It was, after all, a time when the university stood up for academic freedom. Columbia remained behind Professor Edward Said when Zionist activists agitated to have him stripped of his tenure after he was photographed hurling a rock across the southern Lebanese border into Israel. It seems, however, that those days are over.

From ‘Mandela Hall’ to ‘Hind’s Hall’

At the invitations of university administrators nationwide, police clad in riot gear have, over the last few weeks, swarmed campuses, arresting thousands of protesters peacefully calling for the very thing students were demanding more than two decades ago.

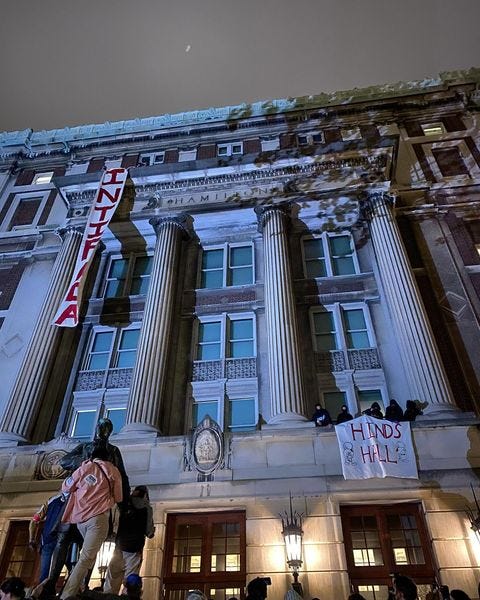

At Columbia, president Minouche Shafik invited the notoriously brutal NYPD in against the very student body she is charged with protecting and appearing to give them carte blanche to carry out the largest on-campus mass arrests since 1968. Some of the most distressing images came out of Hamilton Hall, a Columbia building that students occupied demanding divestment from Israel, financial transparency over the university’s $14 billion endowment, and amnesty for all the student participants. Instead of entering a serious and genuine dialogue over those demands, including divestment, the university allowed police to arrest and assault protesters. According to Students for Justice in Palestine, police pushed one student down the stairs, rendering them unconscious, after which point they were denied medical care.

Despite this disproportionate violence, Columbia students are carrying on a proud legacy. In the last seven months of Israel’s relentless assault and nightmarish genocide, it was footage of Columbia students unfurling a banner renaming Hamilton “Hind’s Hall” after the six-year-old martyr Hind Rajab that gave me an electrical feeling I had almost forgotten: hope. Hind sat in a car with her murdered family, her small voice trembling on a phone line to the Palestinian Red Crescent as she begged to be rescued from Israeli fire only to be killed by them too. “We cannot act for our Palestinian comrades,” the Columbia student communique read, “but we see them; we are with them.” It was signed on behalf of The People’s University for a Liberated Palestine and released on the 206th day of Israel’s genocide.

It was their forebearers who, less than four decades earlier, occupied the same Hamilton Hall for about three weeks, chaining and padlocking its doors shut and renaming it “Mandela Hall” – in order to force divestment from apartheid South Africa in the 1980s. It was their agitation that made Columbia University, in 1985, the first Ivy League school to announce it would sever all financial links with the apartheid regime, committing to divest 4% of its portfolio.

Yale University had an encampment against apartheid, Harvard students occupied the Dean’s office, and activists at the University of California Berkeley launched sit-ins, boycotts, and agitation against their university that lasted a year and a half before the University of California regents pulled about $3 billion dollars out of corporations doing business with apartheid South Africa in 1986. It made history as the largest university divestment in the country and was so significant that after he was released from prison, Nelson Mandela made a special journey to Berkeley to thank his “blood brothers and sisters” for their part in toppling apartheid.

Ultimately, at least 155 American universities divested from apartheid South Africa, bowing to students’ demands nearly identical to today’s: no more business with corporations turning profits from apartheid. It was their action that turned the tide globally and forced Western governments to enact changes they had long resisted. The European community didn’t ban certain investments in South Africa until September 1986, while the U.S. Congress successfully overturned President Ronald Reagan’s veto to impose economic sanctions the following month – more than a year after students globally forced the issue to the forefront.

Today’s pundits who say that divestment from Israel is impossible are, at best, uninformed and out of touch, but mostly, they are pernicious peddlers of a status quo that is dead in the water. It was Columbia students who successfully pressured the university to cut its investments in not just companies linked to apartheid South Africa, but also in private prisons, tobacco companies, Sudan, and fossil fuels.

Why Should Universities Be Allowed Quiet and Calm?

Columbia University’s brutal crackdown on student activists has set off a national movement of student intifadas. Students at more than 150 universities have since set up their own encampments or held protests to rally for divestment from Israel. Students at Princeton took over university property. Mumia Abu-Jamal, the imprisoned political activist and founding member of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party, spoke to students at CUNY, the largest public urban university in the United States, and exhorted them to “not bow to those who want you to be silent.”

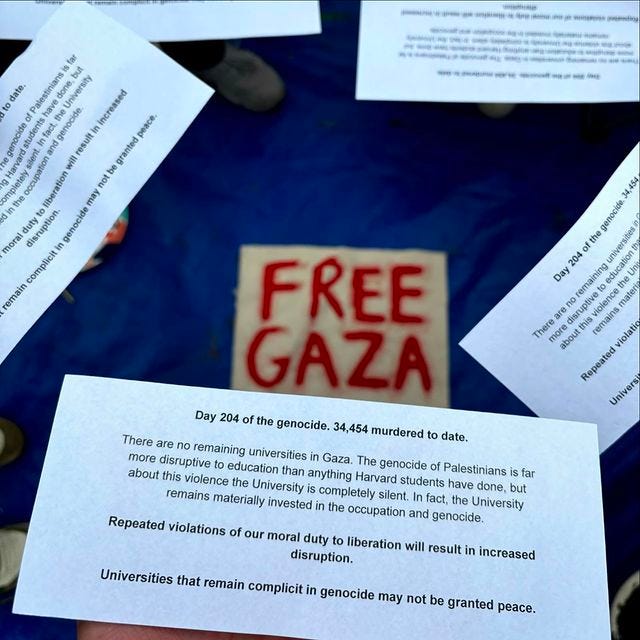

Activists at Harvard – whose endowment is the heftiest at $50 billion – read the names of Palestinian martyrs in Gaza as administrators collected their IDs to mark them for punishment. When administrators handed out disciplinary slips to protesters, they handed their own back. “There are no remaining universities in Gaza. The genocide of Palestinians is far more disruptive to education than anything Harvard students have done, but about this violence, the University is completely silent,” the slips said. They also listed the Gazan death toll – nearing 35,000 murdered at the time – and ended with the following in bold:

Repeated violations of our moral duty to liberation will result in increased disruption. Universities that remain complicit in genocide may not be granted peace.

And why should universities be allowed the necessary quiet and calm so that they may reap the profits of investing in Israeli spyware, surveillance, and weaponry used to slaughter children? It is not a coincidence that Israel has destroyed or damaged 80% of the schools in Gaza and, according to the Geneva-based Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, “systematically destroyed every university,” in the enclave, blowing up the last standing higher learning institute, Israa University by reportedly detonating 315 mines in January. Palestinians have one of the highest literacy rates in the world and have, in the past, been called some of “the most thoroughly educated people in the world.” In its concentrated scholasticide, Israel has targeted UNRWA schools and murdered at least 5,479 students, 261 teachers, 95 university professors, poets, translators, and writers. Students in Gaza have not attended school since at least Nov. 6, 2023, when the academic year was suspended due to the ferocity of Israeli strikes.

I have no doubt that today’s student protesters will be successful. Already, more than 70 public and private universities that make up the Spanish University Confederation have announced they will cut research ties with Israeli universities. Trinity College in Dublin agreed to divest, London’s Goldsmiths College conceded to protesters’ demands, and Evergreen State College and the Columbia-affiliated Union Theological Seminary have announced that they will start or work towards selling all their shares in companies financially invested in Israel’s war and occupation.

“Americans keep wondering what has ‘got into’ the students,” the writer James Baldwin wrote during the civil rights movement and the era of Vietnam war protests, “what has ‘got into’ them is their history in this country.” It was a country whose history was rotten – all the moral and political evidence demonstrated as much. Being educated, both students and teachers, Baldwin felt, had a duty not only to be at war with that rot, but also to transform it. It is telling that Columbia’s students – and university students across the country and the world – have historically risen against the state in protest over its wars, violence, and treacherous policies against the marginalized and impoverished. America’s version of itself as a moral actor in the world is betrayed again and again by ferocious violence in practice. Today, it is not just America’s cold military power that has defended and armed a genocide that the student intifada has exposed, but the nexus between the Israeli military and police brutality, as well as the lies of a media apparatus operating purely in bad faith.

About student protesters, Baldwin wrote in an essay that could be about our present moment, “The great significance of the present student generation is that it is through them that the point of view of the subjugated is finally and inexorably expressed.”