Israel’s genocidal destruction of Gaza’s cultural resources

The Israeli assault on Gaza has not only killed thousands and destroyed much of their housing. It has also led, quite deliberately, to the destruction of much of Gaza’s cultural heritage. The UN Convention defines genocide as the commission of certain acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”, including “causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group” or “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”. Destroying the documents, libraries, religious centres and other monuments of Gaza falls within this definition. See the report below from Karen Attiah of the Washington Post.

Destroying Gaza’s cultural heritage is a crime against humanity

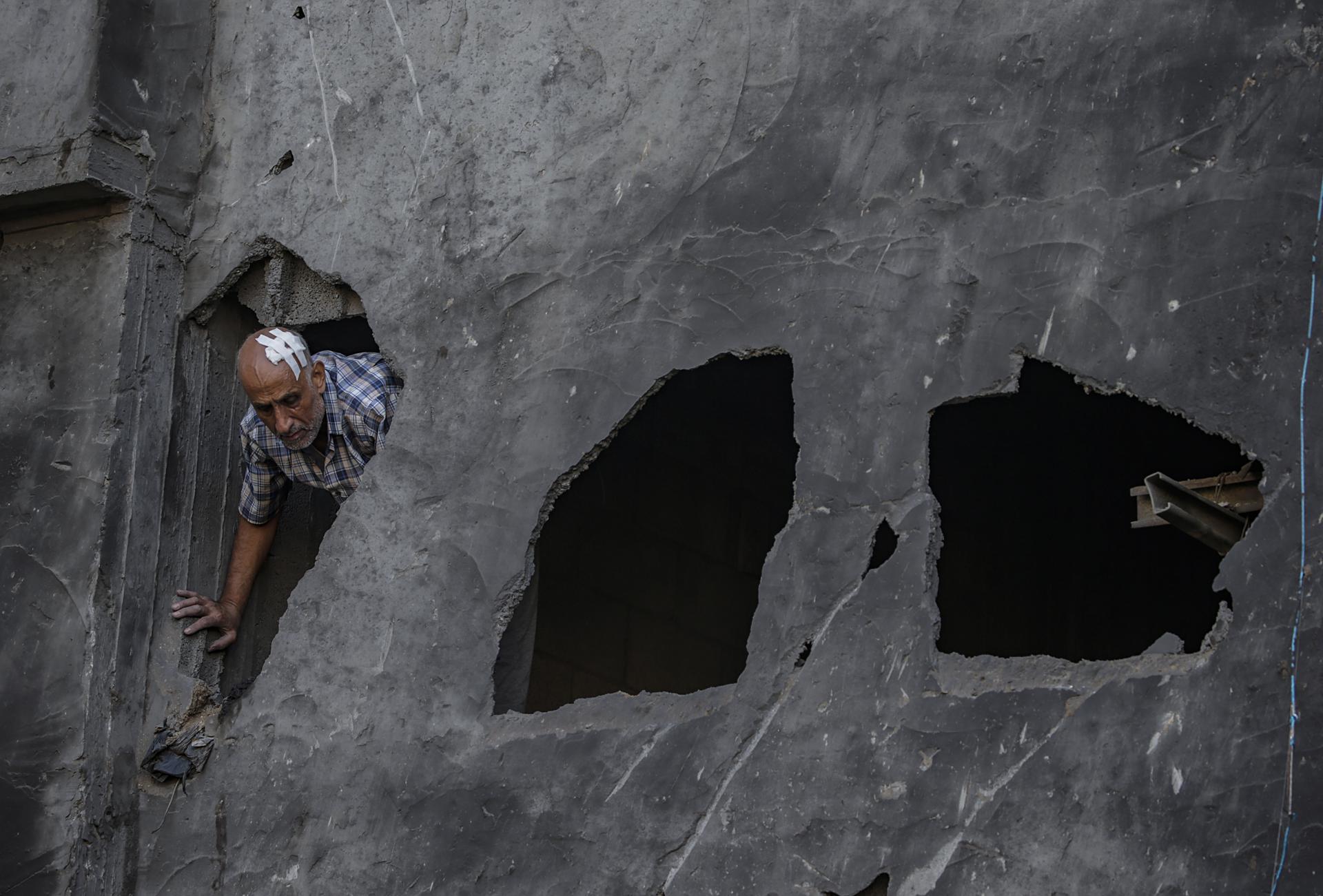

Over the past several weeks, Israel’s assault on Gaza has unleashed all sorts of violence — and not just the obvious kind.

As of this writing, the death toll from the current conflict has passed 15,000. We have seen the images of dead and injured, of people pulling victims from rubble. There has been much global outcry over Israel’s bombing of hospitals, schools and refugee camps.

But one of the less-talked-about aspects of Israel’s bombardment is the destruction of cultural heritage: documents, monuments and artifacts.

On Oct. 19, Israel airstrikes damaged part of the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Porphyrius. Four hundred people had been sheltering inside, and 18 Palestinian Christians were killed. Built in the 12th century, the church is thought to be the third-oldest in the world.

Memorials to prominent Palestinian figures have not been spared. On Oct. 27, the International Federation of Journalists condemned the bulldozing of the shrine in Jenin where Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was shot and killed last year, most likely by an Israeli soldier.

On Nov. 14, video emerged of an Israeli bulldozer in the West Bank demolishing monuments to the longtime Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

On X, writer and translator Lina Mounzer posted a translation of a statement by the Meqdad Printing Press and Library:

“Meqdad Printing Press & Library, one of the oldest in Gaza. Millions lost: printing presses & books & equipment. The cumulative efforts of my entire family: my mother, father & siblings. Gone in an instant; my father left w/ nothing.”

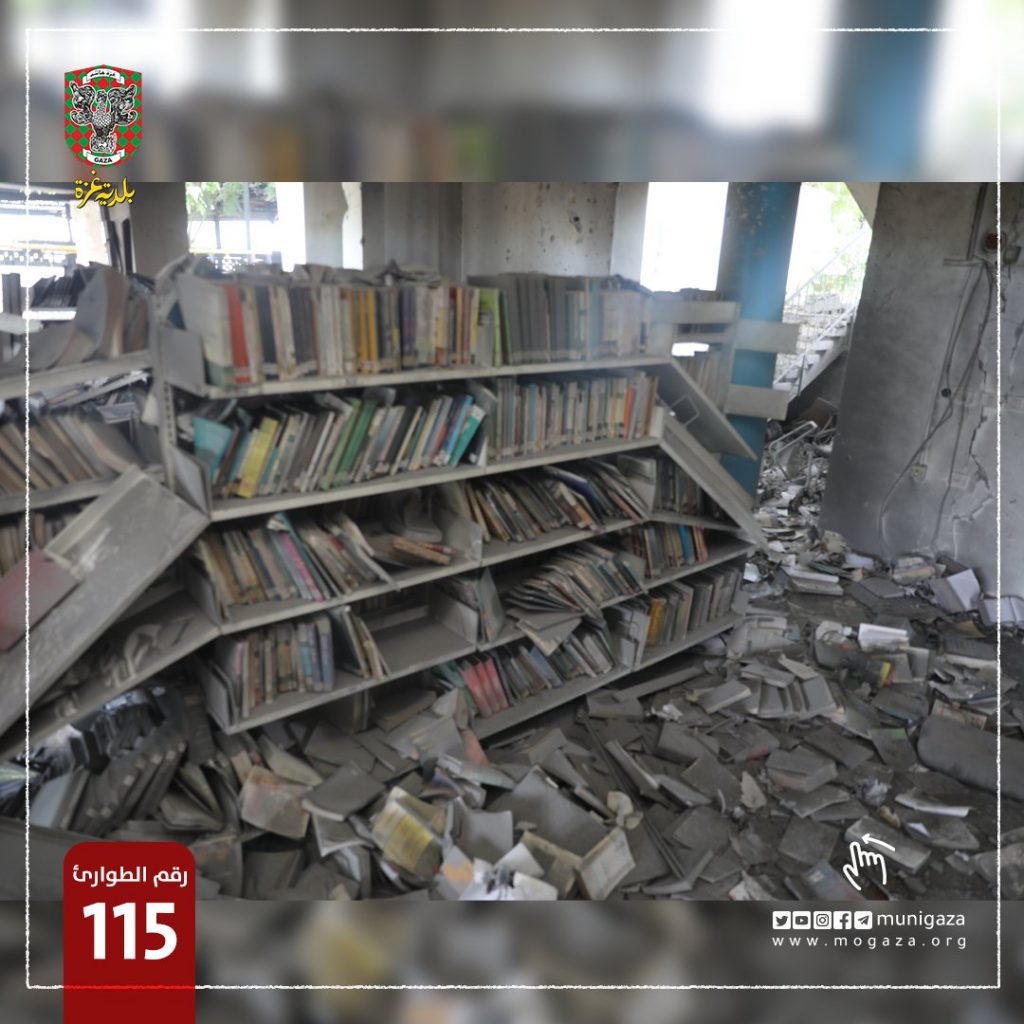

And this week, according to the digital intelligence and sourcing site Storyful, Gaza’s main public library and central archives were ravaged. The Municipality of Gaza stated that thousands of historical documents had been deliberately destroyed and called for UNESCO to “intervene and protect cultural centers and condemn the occupation’s targeting of these humanitarian facilities protected under international humanitarian law.”

Fighting back tears, a Palestinian filmmaker named Bisan Owda posted on Instagram from Gaza about the destruction of the archives, which she said had housed documents that were more than 100 years old. “Now, literally we don’t have anything,” she said. “The future is unknown, the present is destroyed and the past is no longer our past. … Can you imagine that they are doing all these things to destroy the depth of us?”

Under UNESCO’s 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, cultural property is protected under international law. Scholars have long argued that the intentional destruction of cultural heritage is a genocidal act, comparable to the killing and displacement of people — because it results, as one political philosopher put it, in a “loss of a people themselves.”

None of this is new in the history of conflict, invasion and terrorism. Whether committed by the Romans, the British, the Nazis or Islamic militant groups such as ISIS, the destruction of cultural heritage has long been a tool of war and conquest.

Yet again, as with so many issues in the Israel-Gaza conflict, the question sadly arises: Whose cultural heritage — whose lives — are regarded as worthy of protection?

Last year, when Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I and many others sounded the alarm about the destruction of cultural heritage and the looting of artifacts by Russian soldiers. At the time, international organizations and academic institutions were holding discussions and forming task forces to try to help save Ukrainian cultural objects and offer support to Ukrainian researchers.

There has not been much of anything on the same scale for Palestinian cultural heritage in the initial days of the war on Gaza.

I have been talking with scholars who are monitoring the situation from afar, trying to assess the extent of damage to archives, collections and documents. It has been difficult to measure losses because of the lack of communications access. The hope is that a truce or cease-fire will allow a truer estimate of the scale of destruction. But there is also concern about members of the Israel Defense Forces looting artifacts.

It is understandable that amid the horrors carried out over the past 50-plus days, preserving objects and buildings might not be seen as important as protecting innocent life. But the preservation of culture and history is part and parcel of protecting a people and their spirit. If Israel continues to destroy Gaza’s cultural heritage with impunity, all of humanity loses.

Karen Attiah is a columnist for The Washington Post and writes a weekly newsletter. She writes on international affairs, culture and social issues. Previously, she reported from Curacao, Ghana and Nigeria.